The press will surely chronicle the bold-face attendees at the April 20th opening. But they should also pay attention to who doesn’t turn up, for that may signal whether the reign of longtime Met director Philippe de Montebello, 71, will end with well-deserved laurels or a controversy like those which followed his predecessor Thomas Hoving out the door thirty years ago.

Leon Levy, co-founder of the Oppenheimer mutual fund empire, is dead, but his wife Shelby White is very much alive, and is not only a member of the museum’s clubby board of trustees, but of its ruling executive committee, too. She’s also at the center of a long-running dispute that’s tortured the Met and museums everywhere for decades: the ceaseless demands by countries like Greece and Italy for the return of antiquities dug from their soil and smuggled over their borders since the trade was outlawed in the early ‘70s . These nations, and Turkey, Iran, Macedonia and others, see themselves as victims of a network of tomb robbers and shady art dealers who illegally dig up, export and sell their national patrimony to wealthy collectors. Collectors yearn to display their prizes in museums, giving them added value and an aura of legitimacy. The museums say they’re the best equipped to preserve them for posterity — and are unapologetic even when forced to return them.

Last year, the Metropolitan grudgingly agreed to give back to Italy two long-disputed treasures, the fabled Euphronios krater and the Morgantina silver, against the backdrop of an ongoing trial in Rome. Marion True, a curator of the rival Getty Museum, and Robert Hecht, the American dealer who sold the Euphronios krater and other antiquities to the Metropolitan, stand charged with conspiring to smuggle looted antiquities from Italy for the Getty’s collections. That affair, compellingly chronicled in Peter Watson’s recent book, The Medici Conspiracy, cast a shadow over the Met, too. Italy and other so-called “source countries” are said to be looking into its trustee Shelby White, whose collection, scholars have long charged , is full of objects of questionable proveniance.

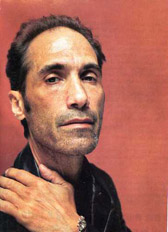

Since his big give-back, de Montebello has voiced scorn for the claims of the source countries. Yet Michel van Rijn, a former smuggler who saw the light and became a trusted advisor of law enforcement agencies, working with source countries, informing against looters and the museums and collectors who buy from them (and also running a crusading web site that exposes and ridicules — with gleeful profanity — looters, dealers and even museum eminences), says secret high-level talks are now going on between the Met and the cultural ministries of Italy and Greece. Those nations want what they claim are their antiquities returned. The museum, van Rijn continues, is eager to insure that high-ranking diplomats of both countries — ambassadors if possible — appear at, and so give tacit approval to, the Met’s new antiquities galleries and the collector-benefactors whose names are writ large over the door. Another deal may be in the making.

“The negotiations are frantic,” says van Rijn, who advises one of the concerned governments. Though White has offered the Greeks the return of nine objects, he continues, “Shelby has taken a firm stand. She wants to go down in history as a great philanthropist, not a looter. She’s pushing the Met in the throat like a goose in France, determined to make her point. She wants a ‘get out of jail free’ card that will make her pieces untouchable.”

The Met has already disgorged two of its highest-profile objects. Will wealthy Shelby — a former journalist who has refused to give me an interview — let her ancient treasures become more museum bargaining chips? The answer may not be apparent until after the last limo glides up to 1000 Fifth Avenue on April 20th.

[If you’d like to share stories — positive or negative — about the Metropolitan Museum of Art, its collections, or the people who created, sustained and now run it, please e-mail me at letters@mgross.com. All communications can be kept strictly confidential.]