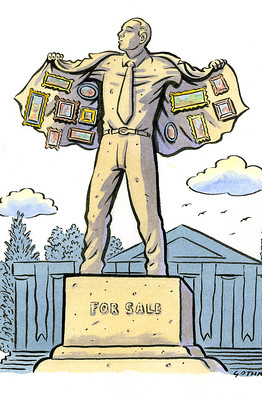

The Metropolitan Museum of Art cut its staff by 357 bodies yesterday, buying out some employees and laying off others in response to the worldwide financial markets. As chronicled in Rogues’ Gallery, this sort of retrenchment is nothing new to the Metropolitan. In the past, though, cutbacks involving human beings have alternated with shutdowns of galleries and trimming of programming. Metropolitan chairman Jamie Houghton is the second Houghton to hold that job. The first, his uncle Arthur Amory Houghton, once ripped apart and sold off pages of a rare Shanameh, the Persian equivalent of the Gutenberg Bible, in order to pay his taxes. (Some of its pages now reside at the Metropolitan.) When that sort of thing is done by a museum, it is called de-accessioning. In related museum news, the Met joined with other institutions to try and impede passage of a bill now moving through the New York state legislature that would impose limits on sales of art from its collections — another typical response of museums to economic difficulties. In its story on that move, the New York Times modestly fails to mention its own central role in calling attention to a massive, secret de-accessioning at the Met more than thirty years ago. But it does point out the central issue involved, quoting James C. Dawson, chairman of the state’s Board of Regents’ cultural education committee, who said, “Cultural institutions hold artifacts in trust for the public.” That’s a truth that often eludes museum trustees.