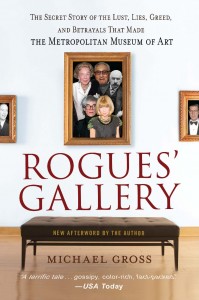

An exclusive story in today’s New York Post alleges that there is a secret deal between the Metropolitan Musem of Art and neighboring co-ops to “scale down big plans for the institution’s iconic plaza.” It apppears, however, that some of those neighbors are not going to lie down and acquiesce to any plan to turn that plaza into a food court. But those who forget–or don’t know–the past are, as the saying goes, condemned to repeat it. Such is the case with the museum neighbor who fumed, “This was a museum of the people. Now it’s the people versus this self-appointed group of elite people.” In fact, that’s always been the case, as this brief excerpt from my 2009 book Rogues’ Gallery reveals:

An exclusive story in today’s New York Post alleges that there is a secret deal between the Metropolitan Musem of Art and neighboring co-ops to “scale down big plans for the institution’s iconic plaza.” It apppears, however, that some of those neighbors are not going to lie down and acquiesce to any plan to turn that plaza into a food court. But those who forget–or don’t know–the past are, as the saying goes, condemned to repeat it. Such is the case with the museum neighbor who fumed, “This was a museum of the people. Now it’s the people versus this self-appointed group of elite people.” In fact, that’s always been the case, as this brief excerpt from my 2009 book Rogues’ Gallery reveals:

“The Metropolitan occupies a state-owned building sitting on public land, has its heat and light bills, about half the costs of maintenance and security, and many capital expenditures paid for by New York City, receives direct grants of taxpayer dollars from local, state and national governments, and for most of its existence has indirectly benefited from laws that allow, and even incentivize, private financial support in exchange for generous tax deductions. So it is clearly a public institution. But even though New York State has statutory authority to supervise the assets of charities—a vague but powerful standard—over the years the Met’s board has considered itself beholden to no one. It has functioned as a private society.

In the Metropolitan’s early days, that meant its wealthy and powerful trustees took a straightforward attitude of “the public be damned,” closing the museum on Sundays, for instance, even though it was the only day that the working class had free for leisure pursuits (and even though the trustees would sometimes unlock the place, Sabbath notwithstanding, for themselves and their friends). Over the years, that arrogance has been toned down, but it has never been entirely abandoned. Today the museum shames visitors into paying a $20 admission fee, even though its lease says it must be open free five days and two nights a week, and its own official policy is that anyone can enter for a contribution of as little as a penny. And although it promised, as part of the agreement with the city that implemented the 1971 master plan, to create open and direct access to the building from Central Park through two courtyards, those courtyards, now named the Carroll and Milton Petrie European Sculpture Court and the Charles Engelhard Court, remain shuttered to this day.”