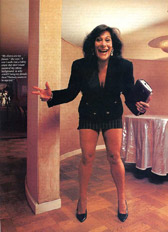

In The Yale Review in 1920, Baltimore’s H.L. Mencken (at right) took on the notion of an American aristocracy, the utter failure of the plutocratic class to live up to any aristocratic ideal, and the role of the press in propping up the plutocracy. This passage is long, but well worth revisiting, as ninety-three years later, it’s both funny and frightening how much it still applies.

“The most salient characteristic of [a genuine aristocracy],” Mencken wrote, “is its interior security, and the chief visible evidence of that security is the freedom that goes with it–not only freedom in act, the divine right of the aristocrat to do what he jolly well pleases, so long as he does not violate the primary guarantees and obligations of his class, but also, and more importantly, freedom in thought, the liberty to try and err, the right to be his own man. It is the instinct of true aristocracy not to punish eccentricity by explusion, but to throw a mantle of protection about it…It is nothing if is not autonomous, curious, venturesome, courageous–and everything if it is. It is the custodian of the qualities that make for change and experiment; it is the class that organizes danger to the service of the race; it pays for its high prerogatives by standing in the forefront of the fray…

“I need not set out at any length, I hope, the intellectual deficiencies of the plutocracy–its failure to show anything even remotely resembling the makings of an aristocracy. It is lacking in the most elemental independence and courage. Out of this class comes the grotesque fashionable society of our big towns….It is out of reason to look for any hospitality to ideas in a class so fearful of even the most palpably absurd of them. Its philosophy is firmly grounded upon the thesis that the existing order must stand forever free from attack…and its ethics are as firmly grounded upon the thesis that every attempt at any such criticism is a proof of moral turpitude…

“Nor has the plutocracy of the country ever fostered an inquiring spirit among its intellectual valets and footmen, which is to say among the gentlemen who compose headlines and leading articles for its newspapers…[The press] is seldom intelligent–save in the arts of the mob-master–and seldom courageously honest. Held harshly to a rigid correctness of opinion by the plutocracy that controls it with less and less attempt at disguise, and menaced on all sides by censorships that it dare not flout, it sinks rapidly into formalism and feebleness…In the more conservative papers one finds only a timid and petulant animosity against all questioning of the existing order…And behind the newspaper stands the plutocracy, ignorant, unimaginative and timorous….Obviously, there is no aristocracy here. One finds only one of the necessary elements, and that only in the plutocracy, to wit, a truculent egoism. But where is intelligence? Where are ease and surety of manner? Where are enterprise and curiosity? Where, above all, is courage, and in particular, moral courage–the capacity for indpendent thinking, for difficult problems?” Good questions, no?