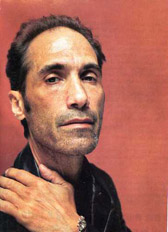

In June 1990, for his forty-forth birthday, Donald J. Trump missed a deadline for a $42 million payment on the bonds that financed one of his Atlantic City, NJ, casinos, Trump Castle, and a $30 million payment on a personally guaranteed loan, and Moody’s Investor Services downgraded the ratings of bonds for the Taj and Trump Plaza casinos. “The 1990s sure aren’t anything like the 1980s,” he reportedly said. He’d just returned from promoting his second book, Trump: Surviving at the Top, when the Wall Street Journal revealed that he’d begun negotiations a month earlier to restructure his debt. In the cold light of the new decade, some of his deal-making no longer looked so artful. He’d paid top dollar and more for properties that, in the mean new economy, were no longer performing. The slowdown hit his hotels, casinos and airline, and real estate sales were especially hard hit by the credit crunch and the disappearance of Japanese capital.

Trump’s bankers were in as much trouble as he was, with credit tight as a noose around all their necks. The “workout” of Trump’s debt, begun when banks loaned him an additional twenty million dollars to make the missed payments and avoid personal bankruptcy, continued for a year and provoked an avalanche of bad publicity. It was gleefully repeated that in December 1990, Trump’s father bought $3.5 million in casino chips to give his son interest-free cash to pay his bills.

“The 1990s are a decade of de-leveraging,” Trump told Time that spring. “I’m doing it too.” In exchange for $65 million in new loans and an easing of the terms on old ones, Trump gave up control of his personal and business finances; brought in a bank-approved chief financial officer; handed over land in Atlantic City and hundreds of New York condominiums; sold his yacht, the Trump shuttle, his half-interest in the Grand Hyatt, and other properties; limited his household spending (to $450,000 a month in 1990, dropping to $300,000 by 1992); and agreed to submit monthly itemized business plans for his bankers’ approval. He got to keep Trump Tower, the Plaza Hotel, the Penn Central rail yard, Mar-a-Lago, and half of his three casinos, though he was forced to reorganize the finances of the Taj Mahal under bankruptcy protection and eventually traded most of his equity in the Penn Central property for release of personal loan guarantees.

“I was in really deep shit,” Trump says in My Generation, newly released as an e-book. “You know, publicity is a funny thing. It does create value. But if things go bad, you get it.” (This is the last edition of the Daily Dose of Donald. We now return to regularly scheduled programming.)