This exclusive excerpt adapted from the 2009 book, Rogues’ Gallery: The Secret History of the Moguls and the Money That Made the Metropolitan Museum, tells the story of the museum’s annual costume party. The 2021 edition of the event will be held tomorrow night.

This exclusive excerpt adapted from the 2009 book, Rogues’ Gallery: The Secret History of the Moguls and the Money That Made the Metropolitan Museum, tells the story of the museum’s annual costume party. The 2021 edition of the event will be held tomorrow night.

The Party of the Year, as it was originaly known, was an annual gala planned to raise $25,000 a year to add to the new Costume Institute’s endowment and, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s board hoped, generate publicity and prestige. The first, held in 1948, honored the designer Norman Norell. The second, a supper dance at the Plaza hotel, featured a show of Belle Epoque fashion. A pageant of wedding gowns was the attraction at the third. At another, the entertainment featured museum director Francis Henry Taylor and a designer competing to see who could transform ten yards of fabric into an evening gown on a model faster; Taylor lost.

Cut to 1961. “I did not invite them!” a later director of the Metropolitan Museum, James Rorimer shouted over the thrumming din of raucous rock music. “Stop them!” The director seemed to vibrate in horror at the frenzy of torsos, twisting in ways he’d only ever seen rendered by the Cubist artists he hated. “I was not aware of this!”

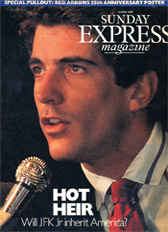

It was the first year of John F. Kennedy’s presidency, and, though Rorimer didn’t know it, also the end of the moated Metropolitan Museum of Art. Francis Henry Taylor’s dream of a broadened, democratic museum was being realized before Rorimer’s startled eyes. The exact hour of the fusty, dusty old Met’s death—9:00 to 10:00 p.m. on November 20, 1961—was noted the next morning in a New York Times article by a young reporter named Gay Talese, who would go on to do more important things (as would the museum). The old Met would march on five more years. But at that moment, as a song called “The Peppermint Twist” echoed through the museum, something changed forever.

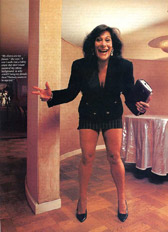

“I was a twister,” boasted Thomas Pearsall Field Hoving, an impossibly tall, lean, eagerly friendly sort with a long, patrician face and an oversized yet impish personality. He has described himself as, among other things, aggressive, selfish, solipsistic, boastful, outspoken, blunt, slightly sinful, impatient, angry, disrespectful of danger, intolerant of hypocrisy, a showoff, a publicity addict, and above all controversial. Although none of that was clear yet—he was then only two years into his first job as an assistant curator of medieval art at the Cloisters—his was the spirit of the age.

Rorimer, though, was horrified and tried to stop the music or at least stop the photographers from taking pictures of the people dancing to pop music inside the temple of art, 750 in all, who’d paid $100 apiece to attend the fourteenth annual Party of the Year for the Costume Institute. It was being held for only the second time within the museum. A year earlier, at the same party, there had been sedate fox- trots and waltzes; this time it was Joey Dee and the Starliters whose sound spilled into the Great Hall, where Hoving and his ebullient wife, Nancy, danced.

After one last ball in 1967, the Party of the Year and the institute itself shut down for a face- lift. The Party of the Year, revived by the CFDA, returned in force in 1974, to coincide with the opening of thr latest Costume Institute head Diana Vreeland’s later exhibition, of couture of the years 1910 to 1940. The party committee was a social who’s who, including Gianni Agnelli, Leonore Annenberg, Pat Buckley, Jacqueline Onassis, and her sister, Lee Radziwill. “From then on, it was the hot party of the season, always held the first Monday in December,” says a friend of Vreeland’s. “It was because of Diana that all the stars came: Babe [Paley] and Betsey [Whitney] and Jane Engelhard, full of rubies.” Though they didn’t know it at the time, that fashionable crowd would soon evolve into the Metropolitan Museum’s most visible ruling clique and would reign into the next century.

Hoving’s #2, Ted Rousseau, courtier of the wealthy, had something like that in mind from the start of his seduction of the sixty-eight-year-old Vreeland. By the late 1960s, the Costume Institute, subsumed into the museum as a department in 1959, had lost its pizzazz as haute couture was elbowed into the gutter by street fashion.

Vreeland, a minor socialite and longtime fashion editor, invited her friends, her world,” says one of her assistants, Katell le Bourhis. “It was international café society.” Vreeland unveiled her most powerful weapon at her 1976 show, The Glory of Russian Costume. Jacqueline Onassis, just widowed for the second time, had always shied away from public display, but she not only served as chairman of that Party of the Year; she published the exhibition catalog, the first book she commissioned in her new job as an editor at Viking Press. The former first lady not only accompanied Vreeland to the Soviet Union while she was preparing the show (one of the five exchange exhibits negotiated by Hoving); she also helped overcome Soviet resistance to loaning objects once owned by the czars. A year later, Onassis wrote an introduction to the catalog for Vanity Fair: Treasure Trove of the Costume Institute, a sort of greatest- hits show. Surveying the two thousand guests at that Party of the Year, its first director, Stella Blum, sagely observed that “fashion cannot exist without a leisure class.” Neither could museums.

With Pat Buckley and Katell le Bourhis presiding and Jane Engelhard’s daughter Annette and her husband Oscar de la Renta pulling strings in the background, the Costume Institute’s parties and exhibits went on after Diana Vreeland died, but in the early 1990s, a new restraint dimmed the proceedings. As the museum searched for a replacement for Vreeland, and fashion lost direction after the giddy 1980s, the Costume Institute lost its fizz. Its exhibition space was cut down by almost two- thirds to make way for a new employee cafeteria. Two new curators were hired, Richard Martin and Harold Koda, who’d put on widely admired shows at the Fashion Institute of Technology, but their first few Met shows were tentative as they tried to find a middle ground between Vreeland’s way and the museum’s. “There is no razzle dazzle,” complained the New York Times. “A little would help.”

Though the usual suspects still paid $900 a head to attend, and Blaine Trump, a pretty and popular new socialite, signed on as co- chair, even she admitted that the soufflé had gone flat. A 1993 tribute to Mrs. Vreeland’s “immoderate” style failed to pick things up. The Party of the Year was “ailing” and “no longer an exclusive evening,” a critic said.146 So the next year, Oscar, sixty- two, and Bill Blass, then seventy- two, replaced Trump as the co- chairmen, albeit without much enthusiasm. Annette de la Renta had been named a vice chairman of the museum in 1993, though, and it wasn’t long before her influence was felt; she and Oscar were about to turn the museum into a vehicle for their social ambition.

In 1995, there was a bloodless coup at the Costume Institute, and Pat Buckley and her older society crowd were nudged aside, replaced by Annette, Anna Wintour, the editor of Vogue, and Clarissa Bronfman, the wife of a liquor heir who’d recently invested in a fashion line. A year later, in what appeared to be an attempt to spread the work and the wealth fairly, the baton was passed to Wintour’s chief competitor, Elizabeth Tilberis, the editor of the rival Harper’s Bazaar, for the opening- night party for a show on Christian Dior, the first in many years that gave off the scent of overt fashion promotion. “Just another tedious, overtouted soirée,” wrote the Times, which added that not even an appearance by the Princess of Wales could “lift the crowd above a certain dutiful enthusiasm.”

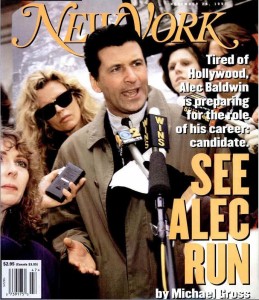

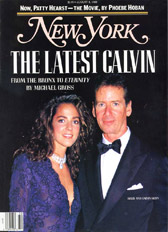

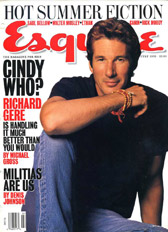

After that, Emily Rafferty and Annette gave the chairman’s role back to Wintour—and the long- playing cast of society characters was permanently replaced by fashion high jinx and low commerce, to the delight of the crowd. In years to come, Wintour’s co- chairmen would include socialites old (Jayne Wrightsman), new (Mrs. David Koch), and in- between (Caro-line Kennedy and Stephanie of Monaco), but more often they would be the ruling class of the new, commercialized simulacrum of society: fashion marketers like Tom Ford, Tommy Hilfiger, and Aerin Lauder and movie stars like George Clooney, Julia Roberts, Nicole Kidman, and Sienna Miller. In recognition of her success, Wintour was named an honorary museum trustee in 1998. Though her importance to the museum was often dismissed by art lovers as negligible, her effect on its image was incalculable. Like fashion, the cast of characters now changed annually and grew ever less exclusive. The Party of the Year, though still a fund- raiser, was now an elaborate costume party, and a marketing opportunity for all concerned.

In 2000, the fashion takeover of the museum seemed complete when a show featuring Chanel was announced, to be paid for by the brand and guest curated not by curators but by Chanel’s designer Karl Lagerfeld, who communicated with the museum through a friend, Ingrid Sischy, then editor of Interview, a magazine fixated on novelty and fame. Worse in many minds, it would be staged not in the basement institute but in the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Galleries, steps from the museum’s European paintings.

But shortly after the show was announced, Montebello abruptly canceled it. Some said he did so because Richard Martin had recently died and would not be there to stand up to Lagerfeld. Others posited that Lagerfeld and Montebello fought over the meaning of the word “contemporary.” Michael Kimmelman, the latest art critic at the Times, suggested that the cancellation was actually caused by a show called Sensation, held the year before at the Brooklyn Museum. An exhibit of new British art from the collection of the advertising man Charles Saatchi, it was condemned as too commercial by museum purists, who accused Saatchi of trying to raise the value of his collection, and as sacrilegious by New York’s mayor, Rudolph Giuliani, who objected to a portrait of the Virgin Mary adorned with elephant dung. The mayor’s opinion was supported in an Op- Ed piece by Montebello, who insisted, under the headline “Making a Cause Out of Bad Art,” that the mayor had a perfect right to judge the show “either repulsive or unaesthetic or both.”

But a mere five years later, Chanel and Lagerfeld infected the Met after all, in a show that Kimmelman called “a fawning trifle that resembles a fancy showroom.” The critic also intimated that by reversing course, Montebello was trafficking in moral hypocrisy. The same week Kimmelman’s critique ran, New York magazine put the Chanelized Party of the Year on its cover. No longer was the magazine criticizing the museum; instead, it lionized the planners and participants, most especially Anna Wintour and Emily Rafferty, who’d just replaced McKinney as president. “The sponsors”—Chanel and Condé Nast had paid the estimated $2 million cost of that year’s party—“give a lot of money,” Rafferty told the magazine, “and we make sure they’re satisfied.” Anna’s Party—as it would henceforth be known—struck a new balance between art, commerce, and society. “At the Costume Institute Ball, it is real taste that counts,” New York wrote. So “in the end, the Met is happy to overlook the implicit commercialism. After all, it gets to play host to a lot of those super- rich benefactors. And amid all the bedazzlement and air- kissing, who would be so crass as to mention a little thing like commercialism?”

Certainly not Montebello or the de la Rentas, who knew that their product, too, was being sold.

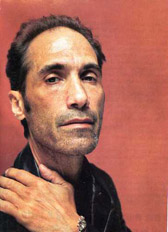

But at the ball celebrating the May 2006 opening of a show of British designs called AngloMania—attended by Charlize Theron, Lindsay Lohan, Sarah Jessica Parker, Drew Barrymore, Jennifer Lopez, Jessica Alba, Victoria “Posh Spice” Beckham, Scarlett Johansson, the fashion- challenged Olsen sisters, and the odd man out, the Duke of Devonshire—a lone voice in the crowd did suggest that the emperors had no clothes. John Lydon, a.k.a. Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols, was determined to make a mockery of the moment.

According to the Times, the “oafish” Lydon, who “was itching for a good fight . . . wobbled around the edges of the party,” insulting guests, offering the sweater off his back—which he’d designed—to Wintour (she “quickly handed it off to a museum officer”), and for his finale, which was not reported by the Times, walked around giving museum guards Nazi salutes and barking “Fashion!” in a tone that made it abundantly clear he meant “fascist.”

© 2009 Idee Fixe Ltd. All rights reserved.