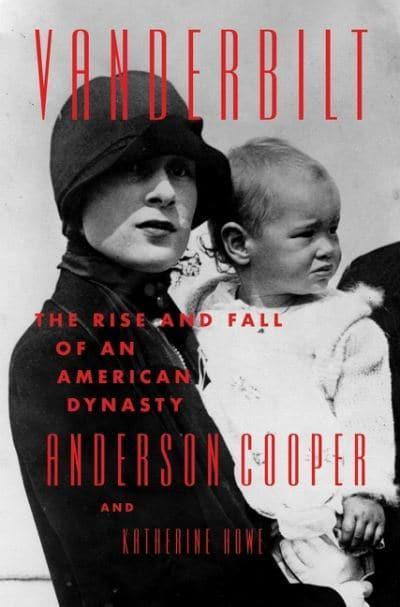

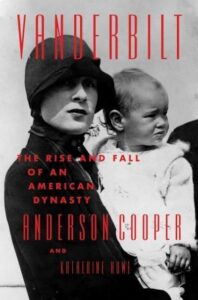

In Fall 2004, I conducted an interview with Gloria Vanderbilt and her son Anderson Cooper for Bergdorf Goodman Magazine. In honor of Cooper’s just-published book (co-authored by Katherine Howe) on his mother’s family, here is that conversation:

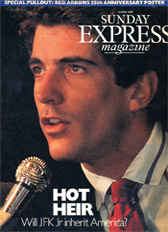

Gloria Laura Vanderbilt, a great-great-great grand-daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt, aka The Commodore, first entered the public eye as the 10-year-old object of a bitter custody battle pitting her penniless widowed mother against her millionairess aunt Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the pedigreed bohemian who founded the Whitney Museum. Nicknamed the “poor little rich girl” by the tabloid press, Gloria grew up to become a beauty, a boldfaced name in her own right, an artist, a fashion designer and a provocative writer. In her seventh book, It Seemed Important At the Time, Vanderbilt writes with tenderness and clarity about her famous lovers (Howard Hughes, Bill Paley, Marlon Brando and Frank Sinatra) and husbands (Leopold Stokowski, Sidney Lumet) but also about herself, about her fourth and last husband, the late writer Wyatt Cooper, and about their two sons, Carter (who died in 1988) and Anderson, anchor of “Anderson Cooper 360º,” his own news hour on CNN. Just before Cooper jetted off to cover a Bush-Kerry debate, BG took mother and son to lunch at midtown’s chic Lever House Restaurant. We wanted to see how they related.

BG: Anderson, did you cringe when you read your mother’s new book?

ANDERSON COOPER: No, I think it’s really cool. It’s sort of a wiser Sex In The City. I kept encouraging Mom to have it be just like you’re curled up with her talking.

GLORIA VANDERBILT: Well, when I’m writing, I like to feel I’m writing to close, intimate friends. I’ve been asked in various interviews who was the “you” that I’m speaking to in the book. It’s whoever is reading the book.

AC: I love the title. I find it sort of gives me hope that if things are going badly, this, too, shall pass.

BG: It makes you wonder what it’s like to have a life that literally, from square one, was not normal.

GV: The person who’s living the life thinks that it’s normal. I thought, well, people don’t really have fathers because I didn’t have a father. And I never thought that it wasn’t normal.

AC: Frankly, what is normal now?

BG: Anderson, did you know all of this stuff already?

AC: I knew most of it think. Some of the details I didn’t know, perhaps.

GV: Anderson was so amazing. I used to talk with him about this relationship I’d had with a married man, and Anderson would listen, and listen, and I’d go on and on and on, and then afterward he’d say, “Tomorrow, same time.” But he always gave me the best advice.

AC: Yeah, none of which you listened to.

GV: No. People never listen to good advice.

BG: The book makes is seem as though your years with Wyatt were the exception in your life.

GV: Well, we had a stable life.

BG: An island of normality. Is that fair?

GV: Well, yes, except again, some people will say I had such a glamorous life. But it doesn’t seem that way to me.

AC: you really don’t have much to compare it to. You’re in the unusual situation where it’s been that way from your earliest memories. I have the benefit of not having the same last name, and therefore I think it’s [been] somewhat easier to fly underneath the radar.

BG: There are a lot of people who don’t know that you’re Gloria Vanderbilt’s child.

AC: That’s true. There’s no reason people would know. I don’t talk about it.

BG: Does being born a Vanderbilt make a difference? It seems you both transcend, in a way, that family.

GV: I never felt connected to that family until I came to live with my aunt. And when I went to live with my aunt, I always felt like an imposter. I felt I didn’t belong there. I hadn’t heard of her until I was 20 and then suddenly there was this whole family that lived in castles and it didn’t seem as if I was connected with it. I’ve recently met a distant cousin called Arthur T. Vanderbilt, who wrote a book about the Vanderbilts, which I haven’t read. Recently there was a guru coming from India–

AC: Oh, lord. Oy.

GV: –to Asia House, who I heard about, and he was here for three days, and he was doing astrology. So I was able to get an appointment.

AC: Where was he doing astrology? At, like, the Plaza or something?

GV: No. It was through Asia House.

AC: Upscale. Okay. It’s very kosher, hmm?

GV: I had to find out my father’s birthday and my father’s dead, and also my mother. And I don’t know it so I checked with Arthur, and I was able to find out because he knows everything about the family. It was sort of fascinating, because I thought, here are my parents and I didn’t know anything about them. So I found out, then I had the astrology and it was a big disappointment.

AC: [LAUGHS] Oh, really? Well, what did you expect? He was no Walter Mercado? Do you know who Walter Mercado os? There’s a show on Univision, which is a Spanish-language station. It’s on every day at 5. It’s a very tabloid news program. And at 5:47 every day they have the daily astrological forecast by this man, Walter Mercado, who has been on public access TV in New York from the time I was born, I think, and we used to watch him when I was a kid. He dresses like Liberace, and he–

GV: –and he wears the jewelry, and–

AC: –and he gives the daily astrological forecast.

GV: –nd he’s a friend of mine.

AC: Yeah, my Mom has actually met him. Hey, how are you?

[John Macdonald, owner of Lever House, arrives at the table. It emerges that Cooper is regular at the restaurant and knows him well.]

AC: This is my mom.

MACDONALD: This is good. It’s very important to have the Mom approval. I don’t do anything until I get my mother to approve.

GV: Oh, you’re so right. You’re so right.

AC: Do you know what you want? [He points at Vanderbilt’s menu.]

GV: What are you going to have?

AC: I’m going to have the risotto. It’s very good.

GV: Yeah, I’m going to have that, too. We’re going to have the risotto, which Anderson says is good. I read, Anderson, your article in Details.

AC: What did you think?

GV: Well, I was riveted, needless to say.

AC: Uh-huh. What about?

GV: Well, about the Ford thing.

AC: Oh, haven’t I ever told you that?

GV: No! And I was also riveted by your perception that I was–

AC: Oh, that was a joke.

GV: Well, no, I know. But what was the word?–“not intrusive”–

AC: Yeah.

GV: …in calling you.

AC: Yeah. You’re not intrusive.

GV: No, no, I know, but I’m not intrusive because I have to restrain myself.

AC: Well, I know! I know that.

GV: Anderson has a piece in the new Details. It’s about, you know, our feelings about our parents and how they influence us and so on. There was one thing in it that I was absolutely riveted by that I didn’t know about, when he was a Ford model and–

AC: I was propositioned by a photographer when I was a kid, and I never told her at the time.

BG: How old were you?

AC: I was like 13.

GV: They called him at the house, and offered him $2,500.

AC: Yeah. That was pretty great bait. I was to go to a hotel room and open a bottle of wine and have some cheese. At the time I just sort of forgot about it. I was insulted. $2,500 is nothing. I expected, you know…well, anyway.

BG: Where did you grow up?

AC: New York.

GV: In Dalton. From birth to Yale.

AC: Yes. They call them “survivors” at Dalton if you make it through. The corps of survivors.

BG: Growing up, was there a point when you became aware of who your mother was?

AC: There wasn’t some day when I suddenly got hit by her name on the side of a bus or anything. To me, she is very different than who other people think she is.

BG: So your mother never sat you down and told you the facts of life: “Listen, one day in school someone is going to say, ‘Your mother dated Frank Sinatra’”?

GV: We never had that conversation.

AC: No. We never did. [LAUGHS]

BG: You still haven’t had that conversation.

AC: I don’t really see the point or the benefit or the need for such a conversation.

GV: Because of the custody case, the publicity I got as a child, I really rarely read anything about myself. We never saw newspapers at my aunt’s. And I don’t read the news [today] if I see my name. I don’t read reviews. I want to stay clear. My publisher called today and said, “There’s something in the Wall Street Journal, and I think you’d like to read it,” and I saw it coming through the fax, and [LAUGHS] I just crumpled it up.

AC: There really is no point. It ultimately is defeating. It’s not beneficial.

BG: You had no choice about becoming a public figure. It was basically done to you.

GV: I think that’s true.

BG: But Anderson, you had a choice.

AC: Yes.

BG: And yet you’ve chosen a public life.

AC: I don’t really think I made a choice of having a public life. I started doing things which were interesting. I worked as a fact-checker at a thing called Channel 1, which they show in junior high schools. I couldn’t get an entry-level [reporting] job. So I decided I had to create my own opportunity. I came up with this plan. I quit and moved overseas and took a home video camera, and made a fake press pass. I had always been interested in combat, places in conflict, and so I just started going to wars. I enrolled in school in Vietnam, and on my way I snuck into Burma from Thailand, and hooked up with some students fighting the Burmese government. After Vietnam, I hitched a ride on a relief flight to get into Somalia and shot some stories there. I put them together, and then I offered them to Channel 1 in a way that it was basically impossible for them not to use them, because it cost them very little. I never asked them if it was okay. I just told them I was doing this. I said, “I’m going to be there; why don’t you look at these things? If you like them, you can air them.” And they liked them. I did that for three years, and then ABC hired me as a correspondent.

BG: What attracted you?

GV: He likes to live on the edge.

AC: I don’t think that’s true. I do like a certain amount of motion. And also, I think you learn things about yourself and about people in places where emotions are very much on the table. You know, it’s very real in Sarajevo. Life and death is very real. TV allowed me to be there, and I got paid for doing that. So the end goal wasn’t so much being on TV. TV was a means to that end. To me, it’s very sad when people who have lived lives of dignity and kindness end up dead on the side of a road, and no one even notices. So I found being in Sarajevo was a privilege. I don’t get why more people wouldn’t want to go to Iraq now, to bear witness to things that are happening.

[Vanderbilt shoots a look across the table at her son.]

BG: That was some look.

AC: Yeah. I didn’t tell her at first when I went to Sarajevo.

GV: Also, he didn’t tell me when he was on a survival course in Africa that he got malaria and was in the hospital.

AC: Yeah. I didn’t see the point in telling her. It didn’t really…I mean…so, yeah…so I never really chose a public life. I didn’t really think it would become a career. Mom is a big believer in Joseph Campbell: “Follow your bliss.” When I graduated college, I asked her advice, and that was the only advice she came up with, “Follow your bliss.” I wanted something more specific, like “Plastics” or something. But in retrospect, it was very good advice. The path wasn’t really clear. I was making choices based on what seemed important at the time. So it worked out.

BG: So many people who are in the media or of the media do it because they feel they don’t exist unless they see themselves reflected back by the media. But Gloria, you’ve spent your life avoiding that.

GV: What do you mean?

BG: It came over the fax machine; you crumpled it up and threw it away. You not only don’t seek a reflection of yourself in the media; you want it to go away.

GV: Let me think about that.

AC: Mom didn’t choose to live in a cottage in Wales and darn socks all her life.

GV: It isn’t that I–

AC: I think you have a drive, and whether it’s–

GV: I have a tremendous drive and ambition to be in the media as far as what I do.

AC: I think we both have a drive and ambition to be creative and to do something which we think is important and which is satisfying emotionally, and which we think has some benefit to others and is a positive force in our lives. For her, it’s art and being creative and writing and painting and designing, and for me it’s a different form. But I think it’s sort of dueling desires: a desire to produce and also the journey is the destination.

BG: It’s about the work. It’s not about what the work can bring you.

AC: Yeah, although what the work brings you is certainly not bad.

GV: I think, too, that if you’re going to have a career, you have to be willing to get out there.

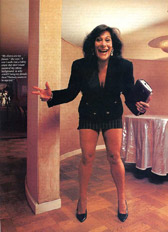

BG: What was your impulse when you started doing fashion?

GV: I started out in home furnishings based on my art. Johnny Carson put me on the Tonight Show and a fabric manufacturer saw it and the next day called and said he thought that the designs in my paintings would lend themselves to textiles. So that’s how I started out. I was one of the first designers that went to stores at that time to meet people. The first fashion thing I did was about three years later, scarves. And then Ben Shaw set me up in business on Seventh Avenue, and I then went into designing blouses and then to jeans.

BG: So it was almost an accident?

GV: Yes, that’s absolutely right. The company had a lot of jean fabric, and I said, “Let’s make jeans. We’ll copy Fiorucci jeans, which I wear, which cost $100, but we’ll make them less expensive.” And a merchandising genius was running this operation, and it was his idea that I do commercials, and–

BG: The rest is history. Anderson, you’re 10 years old at this point.

AC: I’m about 10-11.

BG: And Mom was suddenly doing those commercials on TV. Was that odd?

AC: Not really. It had very little reality for me. It wasn’t as if I sat around watching the commercials all day long. It was a job, what she did. It didn’t really have a major impact on our lives. It wasn’t as if we sat around and talked about it.

BG: Did the other kids in school talk about it?

GV: Wasn’t Ralph Lauren’s son in…

AC: Yeah. There were a lot of kids at Dalton whose parents were in entertainment or fashion. So it wasn’t really a big deal. I’d been in the school since kindergarten, and she had been around and they knew her. Everyone’s parents worked. She happened to be a bit more public than others. I mean, I’ve always thought people’s impression of what her life is like and what my childhood must have been like seems very odd. Their fantasies say more about them than it does about us.

BG: Gloria, you entered the public sphere when you were about 17 years old. You were in the columns all the time.

GV: Yes. I was photographed by Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and all that. It was the period of the glamour girls.

BG: Did it seem benign to you at the time? Did it ever feel invasive to you?

GV: I don’t know. I didn’t think of it in that way.

BG: So you never felt victimized by attention.

GV: Never. I’ve never, ever planned or felt compromised about anything in my life, at all. I don’t believe in that.

BG: Anderson, I don’t know whether it’s odd or it’s fascinating, but it’s one of the two that you ended up (a) a journalist and (b) a public personality.

AC: Well, I don’t think I’m a public personality. I don’t, like, go to functions.

GV: I don’t think of myself as a public personality either.

AC: It’s really just communicating to a camera and talking about news. It’s not trying to become a personality.

BG: Didn’t people once think of Walter Cronkite as an adopted grandpa?

AC: Yeah, but those days are gone. There were three channels for people to get news from when Walter Cronkite was around and there’s now a multitude of not only channels but Internet and magazines and papers, and the audience is much more fragmented. I think it’s better now. I mean, it’s better that it’s fragmented. There are more options.

BG: I think you’re downplaying your own significance.

AC: I work in basic cable, you know?

BG: You work for Time-Warner!

AC: Right. That’s true. And it’s a privilege to be in people’s homes and it’s immensely satisfying, but also immensely humbling and you have to take it very seriously. I mean, I don’t take myself all that seriously, but I do take the news and what I do pretty seriously.

BG: Do you think the fact of who you are and how you were raised gives you the wherewithal to have such a sensible attitude about it?

AC: See, to me the greatest privilege of the way I was brought up was realizing at a young age that what society tells a lot of people to strive for is bull—. It’s not going to lead them to happiness. It’s a privilege at a young age to meet people who have their names in bold print in papers, and to learn that they’re just as unhappy as everyone else and just as confused, and it gives you a sense that that’s not what you have to strive for. That’s not really going to lead you to feeling good about yourself ultimately.

BG: That’s one of the themes of your mother’s new book, although some will probably pick it up for less exalted reasons. There’s something very admirable and brave in dealing in self-revelation the way that you have.

AC: I don’t know that it’s self-revelation. I don’t know if Mom sat down and decided, “Now I want to reveal…” The goal for you is more about, on a personal level, the process of writing. But I do think it’s sort of an optimistic book.

GV: Very optimistic.

AC: …and I think you have a genuine desire to encourage other people and give hope to other people in various ways.

GV: Yes.

AC: So I don’t know that, as you were writing, it was, “Oh, now it’s time for me to reveal…” because frankly, you’re not revealing gory details.

GV: I mean, there’s so much I haven’t revealed. I think the length is sort of perfect. But you know, it’s a valentine, my book, really.

BG: It is. But I don’t sense that you’re pulling any punches

GV: No.

BG: And I would guess that a lot of people in your position would choose privacy over even limited revelation.

GV: Well, I wanted really, as I say, to write in a very intimate, personal manner, as if I was confiding to a friend, and if that is the style you’re writing in, that’s the way it comes out.

AC: To be honest, I think you labor under the fact that her last name is Vanderbilt more than…which I think a lot of people, understandably, do, because it’s a name people know from history books. But to me, that has very little reality. That’s what people pay attention to, but I think that’s sort of missing the point. Though obviously that name has been beneficial in many ways to her, [he turns towards his mother] I think you’ve done a great job of becoming much more than just that. It’s always interesting to me, because I do think people make assumptions based on that name.

GV: Well, you know, Daddy used to say, “The fame cast a long shadow.” And when we met Jackie Kennedy, it was hard to not have that shadow of what one had heard about her. Then once you got through that, you saw that it wasn’t that way at all. And I think that is true with me.

AC: It is fascinating. People’s reaction to fame is very interesting. I mean, I’ve just started noticing more people starting to recognize me on the street. I’ve been covering a lot of hurricanes. In the last six weeks, I’ve done four hurricanes. And a lot of people watch hurricane coverage for whatever reason.

GV: Including your mom at 3 a.m. in the morning.

AC: [LAUGHS] But it’s fascinating to see how people change in their interactions with you. It becomes something else.

GV: It is something else.

AC: I can actually see it sort of happening. To me, it’s very sweet; in some ways, people are very nice and stuff. But I can see how, if you give into it, you become sort of a monster. So I think it’s important to recognize it for what it is, and not let it affect you.

GV: That’s why I don’t read anything about myself. I don’t want to think of myself as being famous.

AC: Because when you do, it starts to lick at you and moisten you and soften you, and it’s very appealing at first. You feel it sort of licking at you gently, and it’s very easy to succumb to it. And frankly, as a reporter, if you do that, that’s the kiss of death. It is so antithetical to what being a reporter is supposed to be about. I used to be able to go and hang out with neo-Nazis and groups and just be a blank slate, and I liked that very much. I enjoyed that most of all. And the more people recognize your face, the less you are a blank slate, and that’s a real problem. [That’s why] I rarely do something like this, frankly. Because it does change the way people interpret you, and I don’t think in necessarily a positive way.

GV: I worry that if I read something about myself, it’s going to be like Lot’s wife, who turned back and turned into a pillar of salt. It gives you pause.