Ashton Hawkins, the beloved, long-time executive vice president and in-house lawyer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, died Sunday at 84 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s Disease. Obituaries for Hawkins have been mostly adoring, dwelling on his work as an art lawyer, behind the scenes operator and arm-twister, and as it chief wealth-whisperer to the museum’s elite supporters. Left out were his role fighting requests for the repatriation of looted antiquities and, as first revealed in Rogues’ Gallery: The Secret History of the Money and the Moguls Behind the Metropolitan Museum, his foiled attempt to take over the job of museum president when William Henry Luers, one of three Hawkins worked under, retired in 1998. Here’s a brief excerpt from those pages of the book:

Ashton Hawkins, the beloved, long-time executive vice president and in-house lawyer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, died Sunday at 84 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s Disease. Obituaries for Hawkins have been mostly adoring, dwelling on his work as an art lawyer, behind the scenes operator and arm-twister, and as it chief wealth-whisperer to the museum’s elite supporters. Left out were his role fighting requests for the repatriation of looted antiquities and, as first revealed in Rogues’ Gallery: The Secret History of the Money and the Moguls Behind the Metropolitan Museum, his foiled attempt to take over the job of museum president when William Henry Luers, one of three Hawkins worked under, retired in 1998. Here’s a brief excerpt from those pages of the book:

It must have rankled Bill Luers when Ashton Hawkins, his nemesis in the antiquities struggle, threw his hat into the ring for Luers’s job. Hawkins felt he’d put in his time and, as the Met’s best widow walker since [former deputy director] Ted Rousseau, deserved the position. “[Former museum board chairman J. Richardson] Dilworth told him he couldn’t have it because he was gay,” says a former [aide to curator Henry] Geldzahler.

Some felt Hawkins had sabotaged his own ambitions. Not only was he gay, but he broadcast that fact “among sophisticated worldly people who thought it was fine to be gay as long as you never talked about it,” says one of his lovers, a little bitterly. “Ashton wrecked his own chances,” the Geldzahler aide agrees, noting what others confirm: “He was drinking a lot in those days,” and word got around. He took to showing up at private parties with “three, five, ten gay men” in tow; they were dubbed the Ashtonettes.

On the subject of Hawkins, the [museum’s] centennial planner George Trescher would paraphrase the poet Lord Alfred Douglas: “The love that dare not speak its name won’t shut up.” But others believe that another gay man could have had the job. Hawkins, whose bloodlines ran back to Colonial times, who had gone to the right schools and had waited his turn, “had been there too long,” says the Met watcher. “He was a throwback to the era when the job was about lunch and coddling.”

Hawkins was kicked upstairs to executive vice president. He stayed at the museum until 2001, but friends say he paid less attention. “He’d spend five weeks in Greece,” at a house he shared with the Cloisters curator Tim Husband, “take three- day weekends, summer was from April until Thanksgiving,” says a city official. “They screwed him, so he could do what he wanted.”

Luers and [the board’s latest chairman Arthur Ochs] Punch Sulzberger both retired on November 11, 1998. Sulzberger was replaced by James “Jamie” Houghton, [former chairman] Arthur Houghton’s nephew, who’d been a classmate of [museum director Philippe de] Montebello’s at Harvard. Luers was succeeded by David E. McKinney, the first non- diplomat to take the paid presidency. A thirty-six-year veteran of IBM and right- hand man of Thomas J. Watson Jr., the son of its founder, McKinney, sixty- four, had retired from the computer giant in 1992. “Other than taking art classes and visiting museums,” Sulzberger’s newspaper noted, McKinney had no background in art. Like McKinney, Houghton was a colorless manager. Simultaneously, Montebello was named chief executive officer, putting him firmly in charge of the museum after two decades as its director.

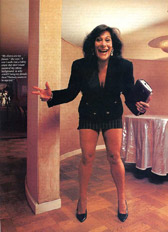

Image from Stair Galleries/Vimeo, “A conversation with Collector Ashton Hawkins