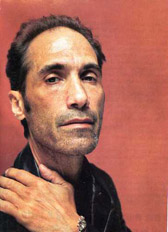

Today, Forever and EverNoMore, the musician, producer and polymath Brian Eno‘s 28th solo studio recording, is getting tremendous attention in serious media outlets. Back in July 1979, this profile of Eno, whom I’d first met in London six summers earlier, just days after he left Roxy Music, ran somewhere somewhat less serious. It appeared in a magazine called Chic, the soft-core porn purveyor Larry “Hustler” Flynt’s stab at legitimacy. Like that medium, and like the glam-rock look of Roxy Music, for that matter, the piece is a bit dated, but Eno’s austere self-image was already set–and has remained consistent ever since. “What we are doing is being artists,” he told me. “We are not entertainers.”

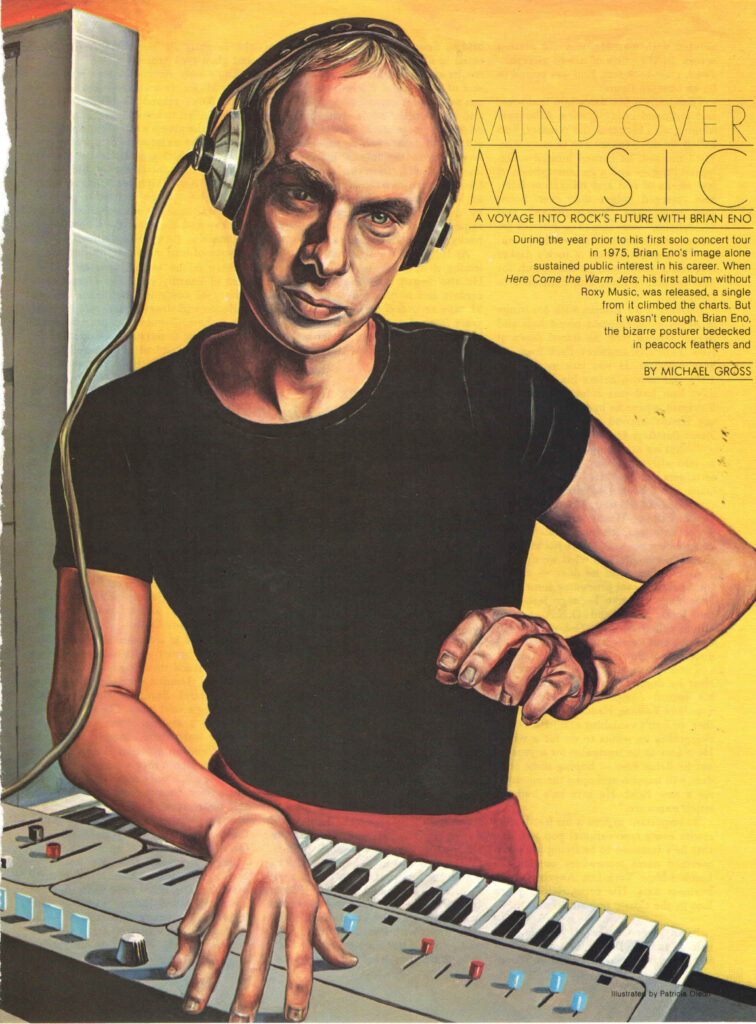

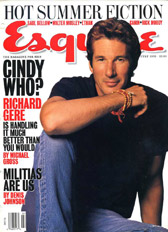

Brian Eno: Mind Over Music

DURING THE YEAR prior to his first solo concert tour in 1975, Brian Eno’s image alone sustained public interest in his career.

When Here Come the Warm Jets, his first album without Roxy Music, was released, a single from it climbed the charts. But it wasn’t enough. Brian Eno, the bizarre posturer bedecked in peacock feathers and painted with mascara, was not getting across. In the guise of a well-merchandised, glam-rock star, Eno was bound to be an obscure figure.

Then, only a few dates into that tour, Eno outfoxed insignificance. After performing with his band, the Winkies, Eno balled six different women in one night. With the last, he earned himself a collapsed lung – and a metamorphosis. A few weeks of rest and relaxation later, Eno emerged bolder than ever. Soon, new terms like “non-musician” and “eclectician” were coined to describe his unique relationship to the world of music. He became a child of rock’s darker reaches, a point man in the search for new sounds. Today, Eno continues to confound.

Looking a bit Roman with his fringe of newly close-cropped blond hair and deeply tanned face, he stared down at New York’s Gramercy Park from his hotel window. It was late in April of 1978, one month before his 30th birthday. Eno had just returned from the Bahamas, where he had produced Talking Heads’ second album, More Songs About Buildings and Food.

“What we are doing is being artists,” he said without turning. “We are not entertainers.” (“We” includes the musicians Eno’s been associated with since the abortive 1975 tour: John Cale, Nico, Devo, Talking Heads and others.) “If we do entertain, it’s incidental. There’s no snobbery about it. We’re not afraid of that. It’s secondary to what we do.”

After doing what he does – during this visit, it meant producing some local New York acts like Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, Mars and D.N.A. for an album called No New York – Eno left the city and hurried to Germany to produce David Bowie for the third time.

Then Eno disappeared. “He’s made it clear he doesn’t want me to call,” said his record company publicist. Chris Frantz of Talking Heads speculated further on Eno’s vanishing act: “He’s done everything he wants to do for a while. He wants to be incognito for a year – not be Brian Eno – hoping some accident will happen and open the potential for a new twist. He says he’s had too much exposure.”

So important to Eno is his freedom to rewire every conventional pop wisdom, that he’s rumored to be living under an assumed name somewhere outside the London-New York-Los Angeles music business axis. His eccentricities place Eno in the classic pop-star tradition.

Brian Peter George St. John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno is the son of a Suffolk, England postman. Born in Woodbridge, Sussex in 1948, Eno was educated in Catholic convent schools. The results are mixed. He has that combination of insight and discipline that rigorous religious training emphasizes. He is also a protracted adolescent, though he no longer brags about his sex life as he did in the days when he regaled interviewers with the tale of his lung collapse. Friends, however, confide that Eno still remains a fan of the sexual arts, no less interested than ever. He comes by the fascination naturally, with the responsibility divided between his two backgrounds – convents and rock.

At 16, Eno left religion for art, transferring to Ipswich Art School to paint. He also began tinkering with tape recorders and is rumored to have owned 31 tape recorders as a schoolboy. Two years later, Eno entered the acclaimed Winchester Art School where he wrote poetry and helped form two bands: the avant-garde Merchant Taylor’s Simultaneous Cabinet, followed by an improvisational rock band named The Maxwell Demon.

After earning a diploma in fine arts in 1969, Eno moved to London where at various times he worked as a designer, an electronics trader and a free-lance porno movie actor. In 1971 he was invited to join Roxy Music, an embryonic art-rock combo with no experience other than rehearsal. Eno signed on-board as “mixer and electronic supervisor.” A year later, Roxy’s debut at a fashionable London party was a smash, thanks to ultra-sophisticated staging and the revolutionary sound born of all that rehearsing. It was quite a change.

Eno changed, too, he remembers: “The technician became a kind of magician, charming audiences with an appealing, sexy, hermaphrodite pose onstage, a walking art object delineated in an exquisitely applied mascara and adorned in gorgeous peacock plumes.” Glitter rock was in its heyday and Roxy was in the forefront. Their two LPs with Eno, Roxy Music and For Your Pleasure, both with Helmut Newtonesque brutal woman covers, were years ahead of their time; along with David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, they were seminal works of the brightly lit but short-lived glitter and glam rock craze.

Eno’s only American tour was with Roxy Music. It is remembered as a debacle. Roxy played 20,000-seat arenas, second-billed to heavy-metal superstars. Though the group wasn’t limp spaghetti onstage, the exigencies of opening unknown will work against any band, especially one as determinedly bizarre as Roxy Music, which featured, in addition to Eno, three virtuosos: guitarist Phil Manzanera, saxophonist Andy Mackay and drummer Paul Thompson. Ultimately, Roxy was defined by the persona of lead singer Bryan Ferry.

Ferry is the world’s greatest proponent of lizardly chic. He dresses in a variety of costumes, but leans toward uniforms and sleazy, shawl-collared dinner jackets. Eventually, he disbanded Roxy Music to pursue a solo career. He recently survived being renamed Byron Ferrari by the British rock press, and losing model Jeri Hall to Mick Jagger. But slowly, inexorably, Brian Eno, the man Ferry fired, became more influential and more listened to than Ferry.

The reason for Eno’s prominence was apparent the moment I met him. It was late in the summer of 1973, a few weeks after he was asked to leave Roxy Music. Like Ferry, Eno was a larger-than-life personality. Like Ferry, he was about to begin a solo career. Like Ferry, Eno’s tie with fame was tenuous at best. Like Ferry, Eno had an ongoing relationship with a sultry, fat-lipped, dark-eyed woman named Mandy (co-star of Eno’s porn films); a management company called EG; a friendly publicist named Simon Puxley; and a favorite hangout, The Speakeasy Club.

Eno lived in a modest approximation of artistic poverty. His two-room flat on Alba Terrace stood just off Portobello Road in London, around the corner from Island Studios, where he was recording a steel band. The night I went along to a session, Brian and Bryan’s Mandy were there, Mandy sitting on King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp’s lap. (The album they were making never came out. It’s only rock ‘n’ roll, right?) Eno’s front door opened on a bedroom. His mattress was on the floor, with a visiting member of the German group Can seated on it. Shelves lined one wall. On them were several miniature plants, a high stack of Japanese hard-core bondage magazines, a collection of dirty playing cards, a few pairs of (as Eno delightfully called them) “dainties” sent by admiring young female fans – he sniffed one, chortling – and a series of notebooks he’d kept since his earliest days: a running commentary on life, learning and art. Pages of intricate math were separated by lyrics, drawings, chemical equations, scores, poems and combinations of all the above.

Lately, Eno had given up notebooks for mini-tape recorders. In the back seats of cabs or in restaurant booths he’d suddenly curl up in the fetal position and murmur into the tiny machine. Its tapes, and a thousand others, filled the second room of the flat. Revoxes filled both the sink and kitchen counters. “Substantially revised Revoxes…” he smiled. I stood watching while Eno toyed with his tapes, tried to play one he’d made with Robert Fripp, failed to make his recorder work and finally sat for an interview.

I began by asking about Luanna and the Lizard Ladies, a new band he was rumored to be the leader of. Eno was mysterious. “The girls haven’t totally lizardized themselves yet. I could be Luanna under the right circumstances.” Then he took an oblique tack and described his latest invention: Kelsino’s Electric Larynx, “a device you wear as a choker on your throat, which ties in quite nicely with the bondage theme that will be quite heavily stressed…”

Luanna and the Lizard Ladies were left behind.

“Now you can be onstage and pose to your heart’s content and still make acceptable musical noises. What seems to have happened to rock music over the past few years is that the concept of virtuosity has become too important.”

But hadn’t Roxy Music been a virtuoso band? Eno disagreed. “They never stressed it. We were more interested in a presentation that moved one physically. My contribution to the group was really one of spirit. I contributed the idea that you didn’t have to work by any technical standards at all. You could start anywhere; be both humorous and, dare we say, profound. We are talking about art. You can say ‘profound’ when you talk about art.

“In Roxy Music, I was as interested in chaos and mistakes as in what would happen if the music was played correctly. No one knew what we were going to do next. We had some kind of ability to stand outside the music and laugh at it.

“The nice thing about rock music is that it’s always developed very quickly. It is able to look at itself from the outside and to laugh at itself and not become reverent about itself – real rock, that is. Novelty is at a premium. Novelty for its own sake is commercially viable. It means that you generate rubbish – quite a lot of it. But you also create people who are paid to experiment….Most art forms pay you to carry out one successful experiment continually, whereas you do have this possibility in rock of moving forward.”

Eno paused for breath. His eyes seemed to wonder if I had grasped his reasoning. I nodded, and he continued. “It’s much easier to communicate sound than it is to communicate any other kind of sensory information. Once the technology starts developing, it snowballs because a market develops for it. It deliberately encourages you commercially to try out new systems of working.

“‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ was an example of pure commerciality leading to a successful experiment. It was a million-seller. But the Beatles were in a privileged position where they knew that anything they did was going to get airplay. People were going to give it two or three listens, not dismiss it easily.

“[Roxy was] culturally aware in an intuitive sense; in a fairly conscious sense as well. We saw rock in a much more analytical light. There were undercurrents even when there was only one major stylistic point of reference. Another thing, we were not at all averse to the idea of stealing wherever we needed to.

“As soon as you combine two disparate ideas into one new piece, you cause them to be completely reassessed. They start appealing on different levels. I’m in sympathy with crudeness. Part of my love for chaos is that all the new ideas come out shrouded in chaos, bumbling and not sure of where they’re going.

“I structure my existence from the point of view of avoiding cosmic boredom,” Brian concluded that night. “Nearly always there’s been something which excites me. I’ve never been on holiday. Rolling your trousers up by the sea….I’m very bored getting away from here and not working hard.”

But he must do something for diversion. “Sex. Really, there’s only two things I do and I recently realized that everything I do is a sublimated form of them. The only things I’m really interested in are sex and music, and I must say I’ve been missing out on the sex these last three days in the studio. I like flirting. That’s really a lovely activity because it is a sheer exercise of wit. These are the only areas in which I like to exercise virtuosity.

“There are so many levels – mental, physical, brutal, skeptical, alchemical, what have you…. Shall we go to the Speak?”

The Speak was the club where London’s creme de la creme creamed. Admission was restricted to top-of-the-poppers and their preferred guests only, please. And Eno was at the top, albeit precariously. He was recording and playing live sets in total darkness with ex-King Crimsonite Fripp. His management group, EG, was appalled; they wanted an Eno album, not a bunch of tracks full of synthesized howling. EG fought the release of Fripp and Eno’s No Pussyfooting and Evening Star LPs. But Eno was adamant: “You always work with a consciousness of what sort of expectations you are foiling.”

“Eno’s a thinker,” says ex-Genesis lead singer Peter Gabriel, in the English music paper, Trouser Press. “He’s a con-ceptualizer, and he’s involved in other disciplines, such as cybernetics, but he can relate them to musical situations. He thinks like an artist and often it is the concept that distinguishes him, not the practical execution. I sometimes feel he almost writes songs and music to justify his ideas, as a means of expressing his theories.”

Jerry Harrison of Talking Heads made the point quickly and succinctly: “Eno has sound ideas.”

Obscure Records was one such more or less sound inspiration. Eno wanted to make obscure records and he didn’t want the “punters” rushing out to buy them, thinking they were hot products from “Enostar.” Roxy Music had certainly been disturbing in its time. Eno wanted to continue to disturb. Here Come the Warm Jets was a concession to popular Brit-rock of the day: glitter and pub-rock. It was likely a concession to EG as well. The single ‘Baby’s on Fire’ (“better throw her in the water”) was uniquely twisted. But neither that disc nor its follow-up, Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, was very well received critically or commercially. No rock pundits proclaimed Eno a messiah. No pop magazines put him on their covers.

When Eno came to America on a promo tour for Tiger Mountain he wore a “Certified Cult Idol” T-shirt to his interviews. He was feted and profiled, pinched, twisted and inspected. He survived, though he didn’t seem to like it much. Perhaps the rock star role promised more than it delivered. And, as always, the resultant interviews were quite unlike the typical pop story.

In 1976-77 the world caught up with Eno. Walls in downtown Manhattan suddenly proclaimed, “Eno is God!” Another Green World, called “pastoral” by one critic, was hailed by all. Tastemakers acquired the Eno taste. Copies of Eno’s own Obscure disc, Discrete Music, made the rounds. It was perfect music to work to, people said. Copies of Oblique Strategies were coveted (see box on page 80). Eno had arrived. No doubt, the next time he recorded, The Village Voice would pan his record. Rolling Stone would finally profile him.

“You design a system and then you sit and ride on it,” Eno would say two years later. “It takes you somewhere. At the point where you surrender control, that’s the point that interests me.

By 1978, Before and After Science had been released; I was interviewing Eno once again. Our meeting was slated for Nassau, where he was producing Talking Heads. I flew there and saw the Heads and the studio, but Eno proved elusive. I could only discover that on Easter Sunday he’d attended services in a native church. Since he didn’t have change for the collection plate, he instead signed his contribution card “Professor Barenoni,” an anagram (as is “One Brain”) of Brian Eno. Of such tales, great journalism is not made. I went home.

When he stopped in New York a month later to remix some Heads tapes, all he cared to talk about was his work. Sex was no longer on his mind. The transcript of the five-year-old interview embarrassed him as much as it interested him. He said he wasn’t like that anymore, and from all appearances that was true. His girlfriend had even gone along to Nassau to cook for the band.

Eno wanted to talk about the role of accidents in the recording process. “I consciously construct the situation so I am watching out for these things as much as the intended things. Underneath that is a sense of what is appropriate. At this moment in history, what do I think would be interesting?

“I’m not interested in self-expression. It isn’t what I’m about. It isn’t what the interesting music of now is about. The public sees music as a technique of externalizing some secret. You can set up a matrix against which other people measure their responses. It presents them with an esoteric object that they plug into for a while. They find out something about themselves. They don’t find that out by assuming all sorts of intentions on your part. They don’t need to know anything about your intentions.”

Art, Eno feels, is construed by its audience as highly serious, resulting from complex artistic intentions. But rock is just the opposite. “People who spend a thousand pounds on a painting don’t want to be told that the guy who did it was just having a good time.” According to Eno, art can’t be eclectic or humorous, but rock music can.

Still, “the popstar thing – that’s a real trap. It offers you no freedoms at all except the freedom to buy a motorboat or something dumb like that.”

Eno’s attitude jibes perfectly with that of the New Wave acts who choose him as their producer in ever increasing numbers. “There’s a lot of cynical old farts who say, ‘New Wave, aw, it’s all shit,’ but that isn’t the case at all,” he says. “There’s a phalanx of New Wave emerging. All hybrids, some strange new mixtures. They aren’t typical of the mainstream of punk. Everybody should be eternally grateful that anything is possible. It really clears the air. Bands like Talking Heads, Devo and XTC you wouldn’t have heard of. There was no arena for them to play in, no group of fans who would trust their music.

“I don’t think it’s some heroic stance I’ve taken. The flow of music I feel myself a part of happens to have been revivified by the New Wave. I’ve always seen myself a part of Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, Bo Diddley, early Who, Velvet Underground, early Roxy – I saw that as a line of development. People are doing these things now very much faster than I ever did, so what should I do?

“There’s a lot of knowledge that can be transferred. I have a broad definition of art and I perceive different kinds of development within it. Any area of activity that involves nonfunctional stylistic change has to be called artistic activity. Fashion, slang, sports. Rock music starts with that end in mind: the intention of deliberately entering that area of discourse we call the arts.”

In 1973, discussing David Bowie’s music, Eno said, “I never listen to it, but I don’t listen to many people’s music. When I’ve heard it, though, I find it better than pleasant. Still, it’s never given me a single new idea.” To Eno, new musical ideas are as important as the recycled materials that comprise “the other 96 percent.” Rock music’s very strength is that it has no shame; a quality oft-mentioned in discussions of Bowie, who approached Eno to produce him in 1976.

Bowie, Eno now says, “made a decision not to be pinned down. He’s a good artist. He maintained his courage. He could have coasted along, fucked about and done nothing interesting ever again, which is what most people in that position do – the Rod Stewarts and Rolling Stones and various others of this world. Pete Townshend said a great thing once: ‘I could have been the Chuck Berry of the Seventies, but I left that to Mick Jagger.’

“Bowie tuned into me with Another Green World, and I to him with Station to Station. Neither of us had been that keen on each other before. We weren’t enemies, but we weren’t a source of inspiration to each other. First he asked me if I’d like to work on the Iggy Pop album. That didn’t come off. He asked if I’d like to work on his. That was Low. I came along quite late in the day. Then on Heroes I was in from the beginning.

“We were trying to apply my way of working to his to see how the hybrid would work. My way was to use whatever was in the studio as the basis. Start from scratch. Both of us realize that if you work things out very carefully outside the studio, you stand the danger of coming in and ignoring entirely any of the chemistry that’s happening inside that situation. It all becomes an obstacle, an interference, and it gives you a very worried life.

“The alternative is to say that this isn’t an obstacle. This is a compositional constraint, just like the fact that a record is only 25 minutes per side. The reason I like doing film music is that there are even more constraints.”

And what was life in the studio like with Bowie? “We’d go to the studio, work for hours on end, and then come back and find ourselves sitting in the kitchen at 6:00 AM too tired to make anything to eat. What Bowie would do was tie a napkin ’round his throat and break a couple raw eggs into his mouth. I thought, ‘Fuck, this is really funny. If only this could go on the album cover.’

“If only people could really see how workmanlike this life is in a way. It’s just going to work and doing things as best you can, and then coming back feeling hungry and tired and breaking eggs in your mouth.”

© Michael Gross, 1979