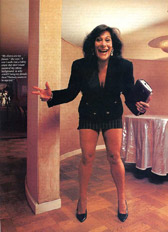

Last week, I nearly crossed paths with Michael Kimmelman, chief art critic of The New York Times, who went to Rome to visit the Euphronios krater, the Greek vase famously smuggled out of Italy, sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1972, and finally returned to Italy thirty-some-odd years later following a lengthy investigation into the illegal looting of antiquities and several high-profile criminal trials. (It’s above, with me.) Even though Times publisher Arthur Ochs Sulzberger was on the museum’s board when the krater was purchased, the newspaper’s culture pages played a heroic role in the affair (a story told in depth in Rogues’ Gallery), following a long tradition of covering the museum without fear or favor, exposing the truth about the krater decades before the Metropolitan grudgingly gave it back. That was then. Now, the culture desk at the Times sounds more like an arm of the museum’s PR office. But I was still surprised to read Kimmelman’s account of his visit to Rome, which echoes the Met’s position that so-called source countries (i.e. the victims of the sort of looting long encouraged and subsidized by imperial museums like the Met) are incapable of properly appreciating or displaying such precious treasures. Kimmelman claims that no one goes to the krater’s new home, the Villa Giulia in the Borghese Gardens (“Italians didn’t seem to care much,” he writes), clearly implying, no doubt to the Met’s pleasure, that the masterpiece would be better off back in New York. In fact, as I discovered when I went to see it and other recently repatriated treasures (from the Getty Villa and the collection of Met trustee Shelby White, among others), this may be a case of sour grappa. The Villa Giulia is a treasure. And Kimmelman’s claims notwithstanding, I wasn’t alone and its compelling exhibits clearly illustrate the damage to historical knowledge done by the long history of looting at archaeological sites.